an old fountain pen resting on a manuscript

Today on the blog, I’m going to dive into a topic that often confuses new writers: the difference between character arcs and story arcs. I’m sure you’ve probably heard about story arcs and character arcs, and it’s very easy to get the two mixed up. So I’m going to clear things up.

First, story arcs and character arcs are not the same, even though you will hear people say that “character is story.” What they mean by that is the character’s development is a huge part of your story, whether your novel is character-driven or plot-driven. Even in a plot-driven story, your character’s changes over the course of the novel make it more readable and relatable.

Your story arc is what happens overall—the sequence of events in your novel. It’s the plot. It’s how your characters deal with the plot that is the story arc. It’s the “what happens” in your story, both in the environment around your character and what happens to your character.

The character arc, on the other hand, is all about what happens to your characters as they navigate these changes—the internal changes. It’s about their personal growth and development, or even their downfall, which is a popular literary trope, as a result of the story’s events.

So, you’ve got two different arcs to think about: the story arc and the character arc. Both of these arcs need to have a beginning, a middle, and an end. For a deeper dive into story arcs, I have podcast episode and a blog post dedicated to that topic. I’ll link those in the show notes for you so you can have another reference.

It can be a complicated topic and one that trips up a lot of new writers or writers who have a hard time keeping all the threads together. Many neurodiverse authors struggle to keep their storyline straight because many of us are pantsers, not big plotters. Having a firm idea of what these arcs are will help you develop a storyline and understand, during revisions, whether something falls under the story arc or the character arc.

Ask yourself: am I making it clear to my readers what’s happening in the story as well as what’s happening to my characters as a result of the events in the story?

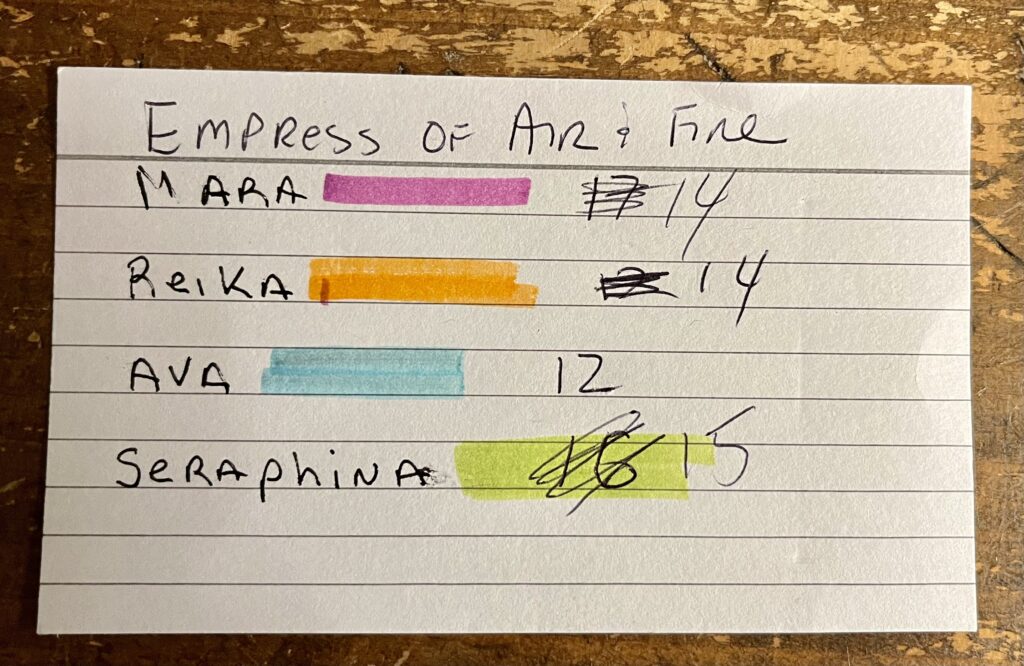

Now, here’s the thing about character arcs—they’re not limited to just your protagonist or main character. If you have multiple characters in your story, each should have their own arc, especially if they are point-of-view characters. Even if the change is small, having your characters go through different changes makes your story richer and more readable.

Nobody changes in a vacuum, and changes in your character often bring about changes in others because the character is no longer acting the way they did in the past. Other characters will notice and react to these changes. You don’t want your other characters to feel like window dressing or placeholders. I’m not saying that every minor character needs a fully developed arc, but the people your character interacts with on a routine basis should have some kind of acknowledgment.

Think back to books you’ve loved. Everyone in those books was impacted by the events of the story in some way, even if the story was told from a single point of view. You often get a glimpse into how other characters change through the narrative, and that’s the kind of depth you want to bring to your own writing.

To figure out how your character will change throughout your story, doing some background work is essential. I’ve got a free workbook on designing characters, which I’ll link below. It’s based on Deborah Dixon’s Goal, Motivation, and Conflict and Eileen Cook’s fantastic book Build Better Characters (Links below). Both of these are great resources to help you flesh out your characters and make them as real as possible.

When your character’s actions make sense, your story resonates more with readers. There’s nothing worse than a character doing something completely out of character without a good reason. Now, we sometimes love a surprising twist, like when the most hated selfish character suddenly sacrifices themselves for the group but even then, we want to see hints of that change coming. It’s those subtle, gradual changes that make a character and your story feel authentic and relatable.

For neurodivergent writers, this process can be especially rich. Many of us have faced unique challenges, often from a young age. Those experiences can be a treasure trove for character development. We’ve often had to be more observant of the world around us, whether to survive, to mask, or to simply understand social cues. This heightened awareness can really help when creating characters who feel real and multidimensional. So lean into that and take advantage of those skills.

Now let’s talk about how to effectively show your character’s change in the story. Because remember, we’re going to show, not tell. That’s what makes a good book. We want to see what happens to the characters. And when I say “see,” I mean we want scenes that demonstrate a character’s change and development. One of the first things you want to do is establish your character’s starting point. That’s the beginning of their character arc. Who are they at the beginning of this story?

Now, don’t info dump. Don’t spill out a bunch of stuff and list every place they’ve ever gone to school and everything else in their lives up until that point. Show us who they are through their actions and their interactions. There’s a great book called Save the Cat by Blake Snyder that explains how to do that, and I will link to that below as well. It gives examples from movies and screenwriting that show scenes filmmakers include to illustrate where a character starts. And they often do this with interactions with other characters—an elderly person, a child, or a random stranger. How they treat other people reveals much about who they are as a person.

The next part of showing your character’s development is the inciting incident—the thing that kicks your novel off. Both the story arc and the character arc are launched here, but they’re viewed through different lenses. There’s the large action happening in the background, the event that pushes your character into the story, and then there’s how your character reacts to that event.

How does your character get pulled into the story? Was it by chance? Did they seek it out? This event sets the story and the character arc in motion and complicates their life with various obstacles. Watching how they deal with these challenges shows us their growth, or lack of it.

Some stories feature a character who never changes, and that’s still a valid arc. It may be a flat arc, but it’s a conscious choice, often used for side characters. Even so, you need to show how others around them react to that lack of growth. Sometimes this kind of stagnation can be just as telling as dramatic change.

So, how do you show those moments of crucial self-realization where the character becomes aware of how their actions are affecting their life? When your character finally starts understanding what’s going on around them, that’s when we as readers see their development. Usually, this happens at the midpoint of the story.

Supporting characters play a vital role here. Remember: Showing how your character interacts with others shows a lot about who they are and how they’re changing. If you’re writing a romance, for instance, this is especially crucial. You want to show both characters realizing they belong together, and their reactions to that realization drive your story forward.

The climax of your story may not always align with your character’s arc. Sometimes, a character’s big change happens after the plot’s resolution, when they take a moment to reflect on their behavior.

For example, in the movie Backdraft, the main character’s development culminates when he honors his dying brother’s request to keep a secret for the sake of the fire department. This significant change happens after his brother’s death and marks a decisive departure from who he was at the beginning of the story.

For longer stories, especially in series, a character’s arc might stretch over several books. If you’re writing a series, you can plot out your character’s development over time. Think of your character’s arc as starting in the first book and concluding only at the end of the last. You can give readers glimpses of that progression along the way, with each book presenting new challenges that keep your readers hooked.

This allows you to stretch out the character development, especially in genres like science fiction and fantasy, typically longer works, where you have more space to explore deep character growth. Even if your character’s growth spans several books, you need some resolution in each one, something that shows their development to keep readers engaged and wanting to know more.

Now, focus on those key moments that will keep your readers hooked and turning the pages. You want your character to be relatable but not predictable. You want surprises and challenges that make readers say, “Wow, I didn’t expect that!” If your character becomes too predictable, readers will lose interest and stop reading.

When you revise, this is the time to polish your characters. Add scenes, dialogues, or events that showcase your character’s progression throughout the story. Make sure your characters’ actions are consistent with who you’ve shown them to be and that their development feels natural.

There are two different kinds of character arc when you’re thinking about revision. There’s a positive arc where the character starts off flawed and grows into a better version of themselves. That is a classic character arc.

You can think of Bilbo Baggins in The Hobbit, who goes from a quiet homebody to an adventurer. And you can also have a negative arc where a character starts off in a very good place and then descends into darkness and becomes the villain of the story and a person you never expected them to become because of events in the story. You can have a flat arc where the character doesn’t change much, but the story around them does. Their reluctance to change and their resistance is also a story. Think about all of this when going through the revision process.

If you’ve sorted your story arc and fixed any problems with your structure, it makes it easier to fit you character’s arc into those events. If you think of them as nesting one inside the other, that can also give you a sort of mental model for how they fit together. They don’t have to exactly align, but they should be close, because your character is changing because of events in the story. So get your story events nailed down first, and then look at your character development. How has that character changed because of events in your story? Are you showing their change or lack of it clearly?

Again, I’m going to include a link in the show notes for a free PDF with 60 ways to show your character’s arc and build that into your manuscript to make your character’s development and clear and compelling.

There are a lot of ways to do show character arc and it can be overwhelming or frustrating at first when you’re just starting out as a novelist, that’s one of the finer points of the process. It is stressful because it’s one of those things where, if you don’t get it right, people close the book. If your characters are not compelling, they close the book—they don’t finish. Or, if you’re trying to get representation, the agent stops reading.

The challenge today is that so many people are submitting, either seeking representation or for publication. If you’re an indie publisher, you have about five pages to capture your reader’s attention. You need to do that by showing a character in those first five pages that intrigues your readers enough to keep turning the pages to find out what happens.

Common author advice used to be you had the first ten pages to hook your readers. In my opinion it’s now down to five, because of attention span reduction, that’s been documented. It is also because of the plethora of available reading materials. The reader can just close the book and go to the next book.So, take your time. Build characters that are compelling and show how compelling they are in that first five pages.

Lastly, I want to touch on a crucial point of character development and creation. Be careful of stereotypes when creating characters. I’ve touched on this in several blog posts and another podcast I have about character development. Stereotypical writing is lazy writing. It does a disservice to your readers and your story. If you’re writing characters outside of your own lived experience, please do the research. Hire sensitivity readers. Talk to people who’ve lived that experience. Don’t rely on stereotypes to fill out your novel. It’s another way to end up in the rejection pile, because readers and editors are not looking for stereotypes. Editors and readers are looking for colorful, creative characters that are compelling, authentic, and nuanced. Creating authentic and nuanced characters is what makes a book relatable and memorable. Think back to those characters that you still carry with you from books you’ve read. The characters you wish you could meet in real life, or those you’re really happy you never have to.

Please, take your time, use your tools, and keep your characters real. I’ve listed a bunch of resources below. Be sure to check out the links list below for resources mentioned in the post.

Until next time, happy writing.

Resources

Sign up for my newsletter for free resources for Writers: https://www.brendalmurphy.com/resources-for-writers.html

Follow me on my socials for quick tips and updates: https://www.instagram.com/writinghwhiledistracted/

Struggling with character development? Check out my free character building workbook: https://BookHip.com/HDPNDMX

Here is the free resource 60 Ways to Show Character Arc: https://dl.bookfunnel.com/xjcaam4085

This is my podcast is all about structure: https://www.podbean.com/eas/pb-ckhgh-167fd45

Eileen Cook’s Build Better Characters: https://eileencook.com/non-fiction/

Debra Dixon Goal Motivation and Conflict: http://www.debradixon.com/index.html

Save the Cat: https://savethecat.com/books

Writing While Distracted Blog on Story Structure/Story ARC https://blog.writingwhiledistracted.com/?p=2295