This is the second blog post in my Steps to Writing a Novel Series. You can find the introduction to the series and the list of steps to writing a novel here. For most writers coming up with an idea is the easy part. In love with their premise, convinced it is a brilliant concept they are compelled to start writing.

They fly along, the words flowing until they hit a bump, maybe at 20k into the manuscript or 30k, most often in the middle of their work. At this point many folks abandon their project and move on to the next shinny idea. This leads to piles of unfinished projects and sadness. Unfinished manuscripts are most often unfinished because time was not spent on the front end of the project to examine the novel’s idea.

A strong premise and supporting ideas are necessary to carry the length of work. It is the number one question to answer before you start writing, particularly in genre fiction because you are working within an expected framework, i.e., in romance there is a happy ever after or a happy for now, in mystery novels you solve the crime, etc. the way you arrive at the expected outcome is the most important part. Readers know how the book ends, it is how creatively a writer arrives at the ending that draws readers to your work.

A premise that might work wonderfully for a short story, will fall short of holding a reader’s attention in a novel length work unless it is expanded and your main characters lives are complicated by events that block their path forward. If this sounds like I am about to talk about plotting, I am.

Although I am a discovery draft writer, I always take the time to examine my idea and then work out a loose plot line based on the initial premise. For example, the idea for my novel Music from Stone came to me one night while we were sheltering in our basement due to a tornado warning. What if my main characters met because they ended up in a basement together during a storm? From there I used the ‘what if/and then’ method, asking myself questions until I believed the idea would support a book length manuscript.

Step one in evaluating any idea is to know what length story you want to write. If you are writing genre fiction, you have to know expected lengths for your genre.

Here is a list of lengths by genre. Caveat: This is a guide, but if you are planning to submit to an agent/acquiring editor/publisher sticking to the expected length can go a long way toward getting your work read by agents, and publishers. If a publisher takes direct submissions, there will be a page with submission requirements, including expected word counts. Stay within the word counts. It will increase your chances of acceptance.

- Mainstream women’s fiction: 90,000–100,000 words

- Thriller: 90,000–100,000 words

- Romance: 65,000–80,000 words

- Mystery: 80,000 words *cozy mystery is usually a bit shorter, 70-60,000 words

- Science fiction: 100,000–120,000 words

- True Crime: 90,000–100,000 words

- Historical fiction: 100,000–150,000 words

- Memoir/Bio: 70,000–90,000 words

- Literary fiction: 80,000–100,000 words

- Young Adult: 70,000–80,000 words

- Middle Grade: 40,000–50,000 words

- Novella 17,500-40,000 words

- Short story 1000-15,000 words

Step two is to use one of the two ways listed below to explore your idea. I have use both of them. Each has its benefits depending on how your mind makes connections and where you are in the story process. I recommend you try each of them to see what fits for you.

- Mind Mapping. Mind mapping is a non-linear way to capture ideas. I use often. My mind tends to go off on tangents before coming back to the central issue I am exploring and in the tangents lie the gold. To assess your premise using a mind map, start with a blank piece of paper. You can do this on your computer, but I find that the keyboard and structure of mind mapping applications slows me down and I lose my line of thinking.

To construct a mind map, write your premise/ idea in the center of a large sheet of paper. Keep it to bare bones, using one or two sentences. When I say large I mean use a poster size sheet of paper. If you write small you can do this on a smaller sheet of paper but I find using a large sheet of paper frees me from rejecting ideas because I have run out of space. If you know the ending of your story because you are writing genre fiction write that in a far corner of the page to keep it top of mind. Once you have the page set up ask yourself the following questions. Write the answers to them around the main premise:

What do my characters do for work?

Do they love their work? Or hate it?

How old are they?

What do my characters want?

Why can’t they have it?

Who are their friends/helpers?

Who are their adversaries?

How do my main characters meet?

What will they do to get what they want?

Where are they?

What time period/setting for the story?

What do they hate?

What do they love?

Why do they want what they want?

What successes have they had?

What failures haunt them?

How deal they deal with failure/success?

What is the lie they tell themselves?

What is the lie they tell others?

*Any other questions you feel are necessary for your project, as related to your characters/story. For example, for my fantasy/paranormal stories I always include questions about magic and its costs, questions about power dynamics, and political systems.

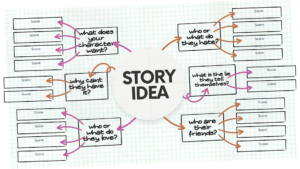

Once you have the answers to the questions completed, draw lines that connect them. From those connection lines write a list of scenes that would show those answers. Example. Your character has failed many times at starting a business. She still believes she can succeed with the right idea. You would list a scene using one or two sentences showing her in conflict with her mother when she asks to borrow money for a new venture provides an opportunity to show her optimism and her conflicted relationship with her mother in the same scene. Here is visual of a mind map with just a few of the questions listed but you can see how answering the questions in scene form allows you to see if the premise lends itself to expansion.

I structure my novels by scenes and plan them that way. As a discovery writer I don’t always know what is going to happen in a scene but I know what the point of the scene is when I sit down to write it. Most of my scenes run about 1000 words.* I am able plan the length of my work by how many scenes I need to tell the story. For a seventy thousand novel I need about seventy-five scenes. {*Your mileage may vary, everyone has different average scene lengths, once you know yours plug those numbers in for how many scenes you will need for your project.} Pro tip: It is okay to have more scenes listed than you need to tell the story, you can pare down the number of scenes once you sort them into a narrative. Learning to mind map has saved me more than once from starting a novel without enough ideas to keep the story from bogging down in the middle.

- Playing ‘what if’/ ‘and then’. This method can be done by hand or on the computer. At the top of your page/document write out your premise. Keep it to one or two sentences.

Ask yourself “and then” and write out your answer. If you get stuck, switch to ‘what if?’ and keep writing using a stream of conscious type flow. Don’t worry about spelling or punctuation just keep moving. Stop when you have exhausted all of the ‘what ifs’ and ‘And thens’ you can think of. This exercise works well as a way to revive unfinished projects too. Be as dramatic/silly/wild/over the top/ as you can with your writing. Once you are finished, put it aside for a day or two, when you look at it again, make a scene list/outline from your ideas. Here is a short example.

Idea: A high powered lawyer returns to a small town to settle her father’s estate and meets the woman of her dreams.

What if they meet because the woman is fostering her father’s dog?

And then they have a one-night stand?

What if the lawyer had a bad relationship with her dad?

What if his business accounts reveal missing money?

What if she goes looking for his account ledgers?

And then she finds his diaries instead and reads them.

What if they reveal he was having an affair with a married woman?

And then someone tries to kill her by burning her father’s house down.

What if the woman she had a one-night stand with offers to let her stay for free at her house? What if she falls in love?

And then loses her job?

What if another attempt is made on the lawyer’s life and the woman saves her?

I also use this method if I get bogged down in the middle of a manuscript or if I feel if the story feels flat.

There are other ways to evaluate your story ideas, but these are the two methods I have found work well for folks with non-linear thinking patterns. Both methods support and harness the creative power of individuals whose thoughts spiral out from ideas and who are tangential thinkers. As helpful as it is discussing your ideas with trusted writer friends, having a record of your plot ideas and a scenes list is essential. It is not a question of if you will get stuck at some point in your manuscript, it happens to everyone, what is important is what you do to get unstuck. When you take the time to evaluate your story idea before you begin you can save time and avoid frustration. Evaluating the idea/premise for a story is a key element for writing success and manuscript completion and is the first step in my list of 12ish steps to writing a novel. Use these methods to keep you writing until you reach those magic words THE END. I hope you found this post helpful. I’ll be back next month with the second in the series. Until then

Happy Writing!